Diving into 2029: a narrative performance

‘David, let’s take a deep breath together’, says Alex Kelly, climate and social justice artist, to begin this fifth Agora: ‘Time stamp: October the 6th, 2029.’ Without further ado, she and David Pledger, artist, curator and critical thinker, casually start to share their thoughts and experiences about life in this future world. Their discussion weaves through history, politics and culture, taking us a few years forward in time. David talks about his ongoing work with a digital human, explaining how ‘our ability to figure out the human from the digital is harder and harder to grasp’. Digital humans have been replacing artists in Australia because of the huge decrease of artist population, unable to find financial sustainability. The dialogue then takes a vivid political turn (especially in the context of Australia): ‘With the development of the Truth-Telling Commissions, in parallel to the Blackfullas University, I feel that discussions about land, country and colonial history are very alive, they don’t feel as fixed as they felt in the past’, observes Alex. This ‘past’ that she refers to is our 2022 present: it becomes clear that their performance carries out a critical approach regarding our present world.

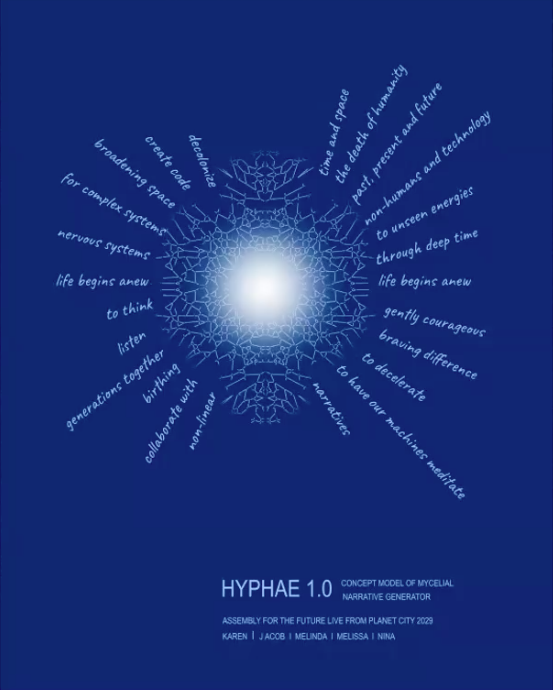

HYPHAE 1.0 Concept Model of Mycelial Narrative Generator: Dispatch by Nina Sellars, generated by Karen, Jacob, Melinda, Melissa and Nina, in response to speculative architect Liam Young’s provocation, who proposed a place called Planet City in which the entire global population moved to one city to let the rest of the planet rewild.

David continues on the subject of colonialism in Australia: ‘The possible dystopian future of an Australian race-based civil war, that some warned us about in the early 2020’s, made us work a lot harder to ensure that that future wasn’t realised.’ Thus, David reminds us of the preventive power of foresighting. ‘Truth-Telling Commission’, ‘Blackfullas University’, ‘Disaster Preparedness Space’… The artists introduce us to new cultural and institutional spaces without describing them any further, letting our imagination project whatever we want into these evocative titles. With a direct but subtle criticism of the liberal system, David relates the caregivers’ strikes that led to a renewal of our modes of relationship: ‘It wasn’t just about care as an economic tool anymore, it became about care as a necessary way of engaging with each other as human beings’. David Pledger and Alex Kelly’s narrative performance goes as far as inventing actual political reforms for the australian society: ‘One of the most interesting and radical things that student strikers did was force the calendar shift of our school years, moving the calendar year to april rather than february in recognition of the hot summer months, and repurposing the school infrastructures as bases of storage and resource use for people’, Alex shares with enthusiasm.

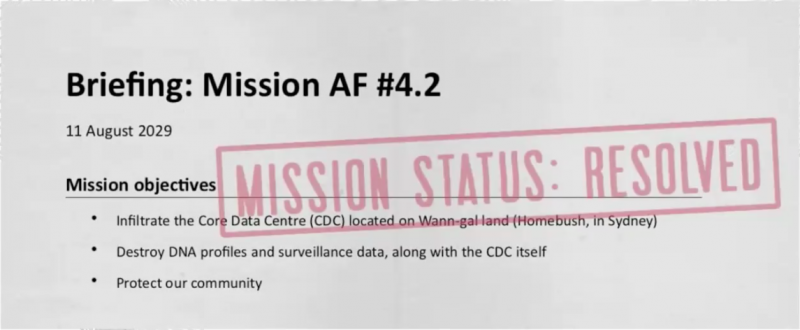

Activist Mission Report AF #4.2: Dispatch from the Third Assembly for the Future, generated by Mali, Jodee, John, Tal, Lara and El, and written by El Gibbs.

After half an hour of dialogue, David ends the discussion on a hopeful note, inviting us to ‘hang in there’ and trust our collective ability to create the changes we want to see in the world: ‘All this seems normal now, when it used to feel like an impossible change at the time’. Like casting a political spell, the two artists project us into a near future in which political mobilisations have led to real changes. The performance’s hidden assumption seems to be: the more you can actually see yourself in a different world - in which what was fearful yesterday has become normal - the easier change becomes.

The original futurists

Welcoming us back to 2022, Alex Kelly reminds us that ‘so-called Australia is made up of over 350 different aboriginal nations’, and specifies that she is located on the Dja Dja Wurrung territory. In doing so, she sets the scene of the highly politically engaged nature of their collective creative practice. Working with first nation collaborators is as important for them as it is instructive, particularly because they have a way of thinking about time very different from our western way, since ‘the apocalypse - British arrival - has already happened for them’. ‘First Nations peoples are the original futurists, we have so much to learn from indigenous futurism’, claims Alex enthusiastically.

Dja Dja Wurrung share ceremony for Yapenya 2018 : https://djadjawurrung.com.au/giyakiki-our-story/

Practising future making

After this artistic immersion, it is time to explain the collective creative practice that Alex and David created together, The Things We Did Next. Their website reads: ‘it is a collaborative practice that generates a series of interconnected artworks and projects based on collectively imagining multiple futures’. What we just experienced is one of many methods and art performances that they (and their collaborators) carry out. Alex Kelly relates how one intuition became the seed that brought the project to where it is today: ‘We are not good at imagining other futures because we are reinforced by our dystopian reality (like the global rise of right wing parties). We must become more disciplined at imagining new futures, to change our determinism’. After meeting with the artist David Pledger, they decided to undertake this purpose together, using art to bring people to practise their capacity to see a larger range of possibilities. The goal is not to design one great future, a singular and better destination, but to invent, experiment, and assume the contradictions and the plurality of what our imaginations are capable of creating: ‘the messier, the better’, claims Alex.

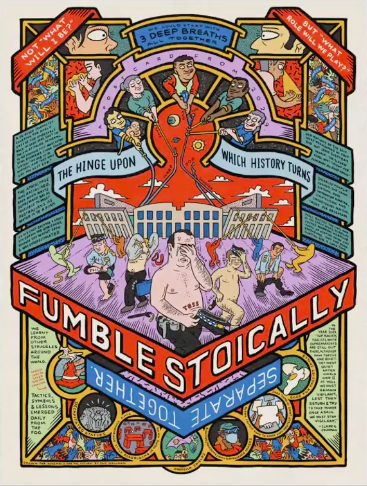

A Postcard from 2029: Dispatch by Sam Wallman from the First Assembly for the Future.

The method

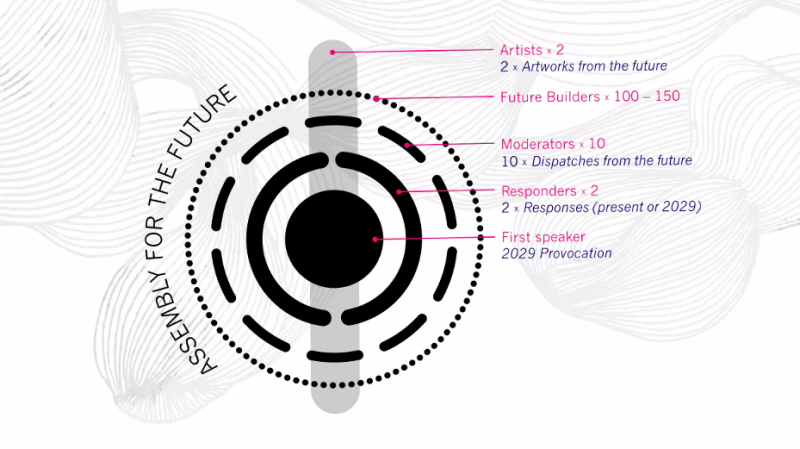

One of the main projects within Alex and David’s practice is what they call the Assembly for the Future, which is a participatory digital workshop of future making. David Pledger explains the dramaturgical strategy of concentric circles used to create disruptive and transversal thinking. The gathering starts with a provocation (resembling the narrative performance they made at the beginning) proposed by an artist: the so-called ‘First speaker’ maps out a future world in 2029. Then, two previously selected respondents improvise a reaction to this call, speaking from the present or the future, thus creating a triangle of discourse. The assembly is then split into 10 groups, moderated by 10 artists who guide the conversations towards embracing collectively a large range of possibilities for the imagination. After one hour of conversation, each artist-moderator delivers a short snapshot of what went on in their group, shortly describing the future that they developed. Artist-moderators are then given a week to generate any form of artwork based on their group’s conversation. In addition, two other artists are invited to observe the Assembly, and are then commissioned to create artworks from the future that inspired them during the Assembly. At the end, the Assembly, generally made up of 150 people - so-called ‘Future Builders’ - produces approximately 2.5 hours of conversations, 1 ‘Provocation’ and 12 artworks called ‘Dispatches from the Future’.

Concentric Circles of Dramaturgy. Read the article by David Pledger.

‘The afterlife of the work is tentacular’, claims David. The Dispatches are openly published on the website, leading to various exhibitions, but also the artists themselves reuse what they created. For example, an artist-moderator created a Centre for Reworlding from one of the Dispatches generated during an Assembly for the Future. The participants usually find it useful to attend these assemblies: Alex relates conversations with activists and political organisers who find themselves rethinking their strategies in a less linear way.

The art of embracing the mess

Every aspect of The Things We Did Next’s practice is designed to embrace the mess, i.e. considering imperfections, differences, and trial-and-error as the most interesting and beautiful parts of life: (1) welcoming contradictory narratives, (2) mixing people from different social and cultural backgrounds, (3) and constantly questioning the biases of the methodology.

(1) Welcoming contradictory narratives: The objective is indeed to operate in the space between utopian and dystopian futures, therefore creating narratives with complexity instead of consensual and binary issues. The plurality of the futures created enables them both to be contested, discussed, and to exemplify the democratic nature of our common future. For them, embracing the mess is highly political.

(2) Mixing people from different social and cultural backgrounds: First, because diversity is a condition for the cultural richness of the narratives. Secondly, the careful approach to accessibility - including that of the design methods - reflects the political engagement of the practice’s initiators. For example, they organised an event with the objective of reuniting generations around future making. Regarding accessibility for socially disadvantaged groups, David Pledger explains that it demands specific work in order to create an environment in which ‘they feel that they have the same agency as everyone else’. While they haven’t been focusing on this issue for the Assembly for the Future project - and are conscious that they could ‘do better’ -, they conduct other artistic projects that address it directly. Each Assembly is an occasion to gather participants that reflect the Australian society, so the practitioners ‘target and send information to various social groupings, especially when choosing artists and respondents’.

(3) Constantly questioning the biases of the methodology: The challenging of the process and the method is an important ingredient of this creative collective practice. Alex and David pay a particular attention to the biases that are conveyed through the narratives that they produce. Attending to the biases in the present which can impact the future is a way both of preventing determinism and reducing the practitioners’ blind spots. ‘We cannot control, we are constantly challenged by the numerous artists and collaborators that participate in the conversations: it’s a way for us to attend to the bias that we have’, explains Alex Kelly.

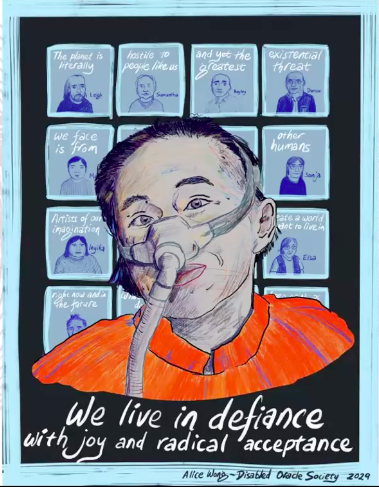

Dispatch by Joshua Santospirito from the Third Assembly for the Future, after Alice Wong’s provocation, The Last Disabled Oracles.

‘Art is a process that cannot be grabbed’

Embracing the mess is also a way of resisting the instrumentalisation of their practice for capitalist means. Art is not used as a tool, but as a method and a process: ‘How do we subvert this idea that art only has a value if it can work as a tool for something?’, asks Alex. She and David are highly conscious of the current neoliberal system through which the value of art has become doing something for the world. David deplores that ‘in Australia, art is often talked about as a commodity, a cultural product, reducing an artwork to a financial unit primarily’. This is due to the fact that ‘neoliberalism shifted from an ideology into an interface, most interactions are now transactions’, continues David. Instead, they decided to think of art as something that is about creating and experimenting processes, conversations and methods.

Defining their practice as a process has the advantage of rendering it resistant to the capitalist approach because ‘a process cannot be grabbed, possessed’, claims David. It is all the more important given that ‘the corporate world has an interest in futurist methodologies to support companies and protect capital’, explains Alex Kelly. In opposition to this approach, The Things We Did Next designed a practice whose goal is to ‘enable new discussions around hope, adjustment and possibility, centering care and justice’, as defined in their manifesto. I can’t help but wonder: if a process cannot be grabbed, but can be told, is storytelling just a new way for the neoliberal doctrine to instrumentalise art?

Seen from the outside, the artworks generated by the practice are intriguing but obscure. One thing is certain: you had to be there, and next time I will!

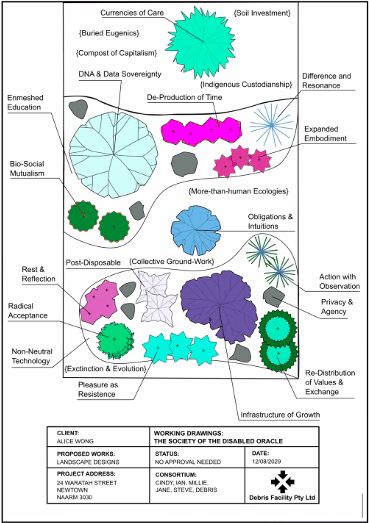

Working Drawings of the Society of the Disabled Oracle: Dispatch from the Third Assembly, from a future generated by Cindy, Ian, Millie, Jane, Steve and Debris.

This online agora took place on October 6, 2022, as part of Narratopia’s Collective Creative Practices project. It was organized by the Plurality University Network (U+), and facilitated by Alex Kelly and David Pledger.

Article written by Juliette Grossmann