The agora is about to start, rock music resounds in the virtual reunion. Just like Rob, the main character in the 2000 film High Fidelity, we share a moment together waiting to the sound of Bob Dylan and The Velvet Underground. As Cristina Ampatzidou from the CreaTures consortium points out, we have another point in common with this fussy character desperately trying to find answers to his questions: “We are list-making lovers!” The people gathered seem to share an interest in the art of collecting projects, stories, initiatives, in order to make them visible, to understand their interconnections, or to create communities around them. Seven collectives are here to share and discuss their experience of making different types of libraries, repositories, and collections of creative and collective practices that pave paths towards sustainability and new narratives. All of them are looking for the answers to the same question: how do we enable positive change?

7 collections, 7 methods, one purpose: transformation

Daniel Kaplan and Chloé Luchs-Tassé start by presenting the purpose, methods and projects of the Plurality University Network (U+), focusing on their digital collaborative library Narratopias that gathers works of fiction, visual arts, speculation, design, or any other form of what they call “transformative narratives”. How do you identify what is transformative, and what can be considered a narrative? Although a definition is available on the website, U+ chose to enable anyone to contribute directly to the digital library. It is a way of saying: whatever effort we make to formulate a definition and therefore draw the essential outlines of the collection, in the end it’s the people’s understanding and use of it that matters. The openness and collaboration seem to self-regulate in a relevant corpus.

Kelli Rose Pearson follows with the ReImaginary Project, defined as a “search for practices, metaphors, mental models, and narratives that support ecological regeneration and the well-being of future generations”. They have multiple matters: making visible different types of intelligence, including non-human and marginalized stakeholders, combining pragmatic and “enchanting” approaches, and connecting with the depth of our feelings, values and beliefs. Kelli explains that “change comes from the inside out”, from the enlivening feeling of engagement that certain experiences activate. ReImaginary collects and makes accessible methods (among which a toolkit of arts-based methods) that enable this type of transformative experiments, organized according to the five steps towards change described by Theory U (convene, observe, reflect, act, harvest). Nine transformative mindsets emerged from the research around the project, such as “Expanded spheres of care” or “Intersectionality”. If “creative methods are morally neutral”, as Kelli defends, it becomes essential for a project to assert its political purpose.

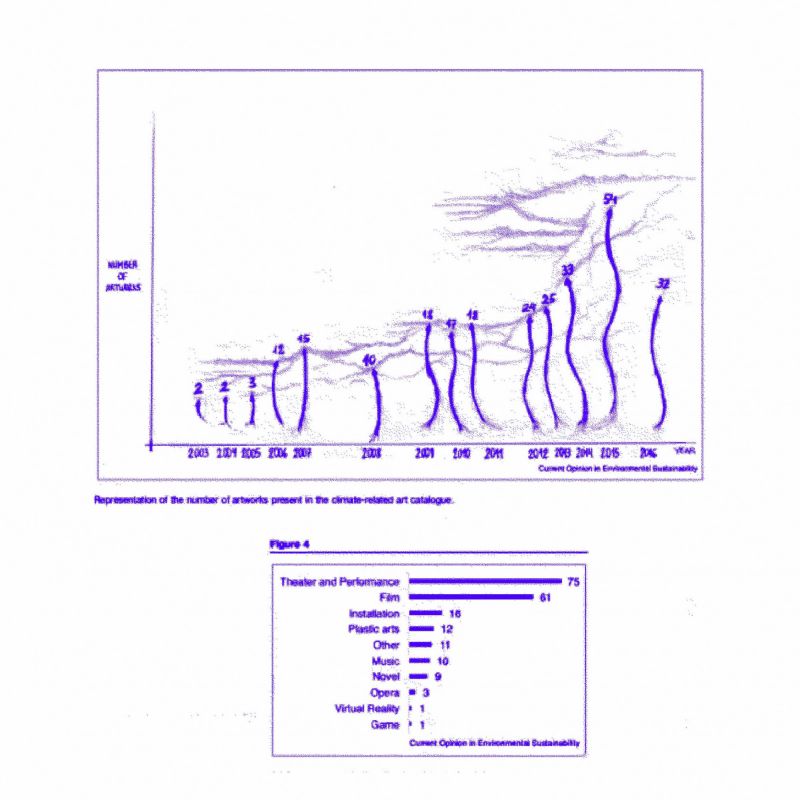

A spectacular Baining fire dancer appears on our screen, with this question written: how can the arts contribute to realizing the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)? The arts that Diego Galafassi and David Tàbara are looking for include any kinds of arts-based research approaches and creative practices, at the intersection of different types of knowledge: scientific and experimental. Starting from an analytical catalogue focused on the climate crisis, the Living Catalogue of the Arts for Sustainability Transformations network adapted the project to the SDGs. “Living” both because anyone can submit an entry anytime, and the catalogue itself is enlivened with interviews, portrait films and workshops. Either by making the interface between arts and sustainability science visible, or by looking for different ways of learning and creating scientific knowledge, the catalogue pursues a single purpose: “to turn passive audiences watching the drama of unsustainability into empowered actors engaged in SDGs”. Two main challenges surface:

“How to turn repositories into actionable knowledge?

What is the value of such a repository for artists and practitioners?”

Romain Julliard, from the research project Mosaic, introduces on our screens an adorable – and critical – hedgehog, who reminds us that this is not about big data and artificial intelligence, but about quality data and collective intelligence. Mosaic helps collective projects in the conception of data exchange platforms, using participatory science methods. For example, they created a protocol to collect data on hedgehogs’ state of health in France, allowing anybody to observe the animal in their garden, share the results on a platform and be part of a collaborative research project. The data is as useful to science as it is fun to collect for the participants, creating a community of people interested in their garden’s biodiversity and willing to contribute to citizen science. Romain shares the secrets to their success: encouraging comments on the platform, allowing different kinds of data to be shared (quantitative and qualitative), and having the data validated by other participants. Romain is currently working with Joffrey Lavigne, here to present the Comité de Science-Fiction (Science Fiction Committee) that mobilizes artists and students to produce science fiction art, imagining new relationships between humans and nature. Mosaic and the CSF are collaborating on the conception of a platform for facilitators to share and discuss their methods for creative and collective practices. Using participatory science methods seems like a fertile idea, in view of the emergence of a community of practitioners.

“What do artists know?”

Embedded into political programs, artists bring new perspectives and creative processes to projects addressing climate change. This answer from the artist Frances Whitehead inspired the creation of the Library of Creative Sustainability that Lewis Coenen-Rowe is now presenting. The main audience for this collection are “those who can take on similar projects” (e.g. local communities, public agencies, community organizers, etc.), by re-using the information from the case studies: all the details of processes, difficulties, tools, etc… Art-lovers are welcome to use the catalogue, but the real purpose is to encourage non-art sectors to trust artists on their ability to think differently and practically. “Show, don’t tell” is the phrase guiding the elaboration of the library, aiming to show how deep collaborations with artists help achieve efficient – and often surprising – sustainability outcomes.

“Our project aims to expand the range and diversity of better anthropocenes”, explains Garry Peterson, Professor at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, up next to present his repository project. In his eyes, there is an urgent need to propose other visions of the anthropocene than what Mad Max and other popular dystopias offer. “We build the future based on seeds of desirable futures that exist today”, explaining how Seeds of Good Anthropocene went from developing desirable scenarios for the future, to collecting existing elements, seeds, that could compose these better futures. To be considered a seed, an initiative must “exist (at least as prototype), be marginal (or not yet mainstream), and contribute to creating a sustainable future (according to someone)”. The term seed is all the more relevant for a project focusing on humanity’s connection to nature all over the world. If “big changes come from below, but are crushed by the dominant narratives”, as Garry believes, it is essential for these seeds to recognize one another and “catalyze transformation by connecting people”. Workshops based on “seed cards” created from the project’s collection, allow participants to make these connections. But on one condition: that they integrate the disagreements that arise on what the future will look like.

“How can creative practices contribute to positive social transformation?”

In their own way, each one of the speakers above addressed this question, but the CreaTures research project that Lara Houston is now describing focused on answering it directly. Using different methods (literature reviews, sector mapping, networking, interviews) to gather case studies of projects that creative practitioners and interdisciplinary researchers considered transformative, they managed in a second phase to analyze them and identify 25 transformative strategies. From “ecological interconnectedness” to “friendship”, these strategies are detailed in articles and interviews, making them more accessible than a cartography of 160 case studies. Sometimes, less is more, even in list-making.

It seems that this abstract from the Dark Mountain Manifesto (one of the projects identified by CreaTures) sums up the purpose of the different projects presented:

“Together, we are walking away from the stories that our societies like to tell themselves, the stories that prevent us seeing clearly the extent of the ecological, social and cultural unravelling that is now underway. […] And we are looking for other stories, ones that can help us make sense of a time of disruption and uncertainty.”

Common challenges

From the discussion after the presentations, five challenges emerged:

1. Managing a common resource

A catalogue is even more demanding in terms of maintenance when it is collaborative and alive. Alive in the sense that none of the repositories presented are meant to be archives, but rather catalogues of objects that evolve, that we can enter in relation with. Keeping the catalogues useful and relevant means spending a great amount of time on checking and updating the data. Specific time and skills are rarely assigned to this “laborious work”, depending on the governance and the financing of a project. It is then up to the goodwill of organizers to ensure that necessary maintenance occurs, taking into consideration that they “each have different motivations for the time spent working on the library”, as Kelli Rose Pearson reminds us.

2. Placing knowledge into context

What is the difference between a manual and a collection of case studies? Placing knowledge into context. The reusability of the information you find in a collection of projects is not evident: “what type of practices work well, for what, in different contexts?”, Garry Peterson asks. The way Lara Houston answers this challenge is to “cut the ties” by pointing out directly which elements can be reusable within each case study. Lewis admits that the difficulty for each project is:

“to find a fine balance between showing sustainability outcomes (technical, quantitative, what actually happened in a specific context) and lessons, tips, and advice (qualitative, replicable information)”.

Maybe the answer is in the interface: if a scientific or artistic project always responds to its particular context, the purpose of the interface of the repository must be to enable the embodiment of the information presented (using interviews for example). Kelli salutes the humility of collecting experimental initiatives because the most important thing is to “embrace the uncertainty of experimenting” and stay ready for surprising outcomes.

3. Evaluating the experimental

Can you collect without evaluating? Garry’s answer is a firm “no”: “the act of picking one project versus another is an act of evaluation; as soon as you have a collection, it is a kind of validation”. It then becomes essential to make your criteria visible and look for experiments which satisfy the conditions you set. This appears to be a paradoxical task for people who precisely collect experimental initiatives. Diego Galafassi and Daniel Kaplan agree on the fact that it is impossible to judge a project from an external point of view, even less with an objective criteria, so the questions become:

“Are the projects taking time to self-evaluate?”

“Are they verifying the goals that they set for themselves?”

There are no means of evaluation other than the claims of a project’s initiators or participants, or maybe looking for secondary sources to triangulate the information collected (which can make sense if pursuing a scientific approach). Or could a qualitative criteria like inclusivity be a way of measuring artistic practices? Lara concludes by reminding us that “it takes time and multiple tentatives for an initiative to be stable enough to be evaluated so it is essential to nurture the experimental, especially in crowdsourced libraries”.

4. Reaching an audience

Who is actually using the libraries, and what for? Any collection initiator must reach an audience to make sense of their work. Some of the speakers started their library to satisfy a surprising interest from different people for methods and examples, like Kelli who “was shocked by the enthusiasm for the toolkit”, and decided to create an abundant website of methods. “Collecting data for the common good is one thing”, qualifies Romain Julliard, but to create real engagement around a participatory project (whether it’s a collaborative library or a participatory science project), you must “focus on the process of the crowdsourced deposition”. Participants must find at the same time an immediate interest (learn something), and a sense of belonging to a community of participants. Designing the interface by putting yourself in place of the users is crucial, keeping in mind that possibilities of use often go beyond what the collections are envisioned for. The Narratopias library, for example, is knowingly used by practitioners to nourish their practice, for workshops or teaching, or by people who seek inspiration to build upon, but maybe it is also used for research or other means.

“How then can we create spaces that can have multiple uses?”, asks Diego.

Two approaches emerge: aiming for the right person in the right place (focus on relevance), or making it as diversified and uncomplicated as possible (focus on accessibility). What better than a spontaneous testimony from the audience to settle the matter:

“I’m Inga Hamilton, a practicing artist currently doing my PhD and these repositories are going to be a huge and valuable resource for me. It brings methods and research together from like-minded people and highlights successes and pitfalls. A selection of curated libraries that feel like a gift!”

5. Creating a community

Like-minded people, yes, but does that make them a community? Chloé Luchs proposes the idea of finding a common language, symbols and typologies, to create a continuity between the different repositories. “I am skeptical”, replies Garry, underlining that “it’s useful that words have different interpretations, it enables comparison and articulation of the differences, making visible the theories of change behind the words”. Identifying different collections with different goals and processes makes them reflect on their own assertions. But if “we want to make transformation happen […], we have to upscale multiple synergies”, asserts David Tàbara. Daniel follows:

“There is a field of practice that is trying to emerge and can grow wiser and bigger. Behind all these lists there are people and experiments, it’s actually a huge community whose members, in many ways, are pursuing the same goals. How could it lead to collaboration and common visibility?”

Meeting in an Agora seems like a good start. Lara concludes with enthusiasm:

“We could organize virtual coffees to share taxonomies, strengths and weaknesses of methods. There is a huge potential for comparison, looking for consensus and dissensus, sectorial and cultural differences. Is there a catalogue of libraries in the making?”

One thing is certain… They truly are list-making lovers!

This online agora took place on March 3, 2022, as part of Narratopia’s “Collective Practices” project. It was organized by the Plurality University Network and the CreaTures consortium, and facilitated by Lara Houston and Chloé Luchs-Tassé.

Article written by Juliette Grossmann