Washington DC (USA), Goa (India), Berlin (Germany), Paris (France), Thane (Maharashtra, India)… The participants for this eighth Agora are attending from different places in the world, all ready to go Beyond the Binaries with artist Adwaita Das, facilitating from India. The purpose of this online workshop is to identify dominant binaries structuring our familiar narratives, hack them by reversing them and playing with them, and then develop the new images and stories that emerged. Let’s make subversive poetry!

Reverse, rewrite, redesign

The first step of the process is to identify popular narratives from works of fiction (or not) that use ‘oppressive’ binaries (i.e. divisions in our belief system that have caused historical damages): the North countries (cold, rich, good) versus the South countries (warm, poor, bad), the mixed versus the pure (like the ‘half-bloods’ discriminated against in the world of Harry Potter), the good and light versus evil and dark (India’s Diwali, festival of lights celebrating the destruction of evil)… Sherein, a participant, reminds us that in the Indian Ramayana, depicting the battle between the noble Rama and evil Ravana ‘Ravana is dark-complexioned, while Rama is fair. The word fair itself is problematic…’. Fair indeed means at the same time ‘reasonable and right’ and ‘pale-skinned, pale-haired’. Once we’ve set off, it’s hard to stop listing the oppressive binaries, one leading to another without ever ending.

‘Binaries are everywhere, how we see colors, how we phrase things, and they are associated with good or bad. [Through this workshop], we create a space where we open up to going beyond these given norms. We find other possibilities, other solutions; and our current way becomes an old way again’, Adwaita explained to me while we were preparing the Agora.

It is thus the time to rewrite these dual symbols. Adwaita proposes a series of different and unfamiliar word associations: pink power, grey goodness, dreamy darkness… Each of us come up with different images and ideas that convey and evoke these new, strange – uncomfortable, in a way – representations. Surprisingly, we find that we can rapidly feel at ease with them, relate to them, expand our imagination and seek out our own experiences that make sense of them.

‘Safe Purple - These words sound good and soft. Safe purple. Where blue and red come together. They would go gentle into that good night. My brain seems fried. But I like the feel of that color’, Chloé shares with the group.

For the last part of the workshop, we are free to explore the new images by developing stories around them. This is about redesigning, which means giving them a form, with fictional writing or whatever artistic media we feel adequate. Adwaita believes that redesigning the way we tell stories and the images we use enables individuals to reshape their identities – i.e. the stories we tell ourselves and others about who we are – towards wellness (for oneself) and peace (with others):

‘I worked in several professions, understanding narrative making. Now I work in mental health organizations around wellness. How we think, feel, affects our existence. Being aware of it, we can reshape it. I love Sci-fi and fantasy, speculative literature, taking distance, rewriting the world. Becoming aware of how we tell ourselves stories, our narratives, our symbolism, allows us to rewire ourselves, like robots becoming free.’

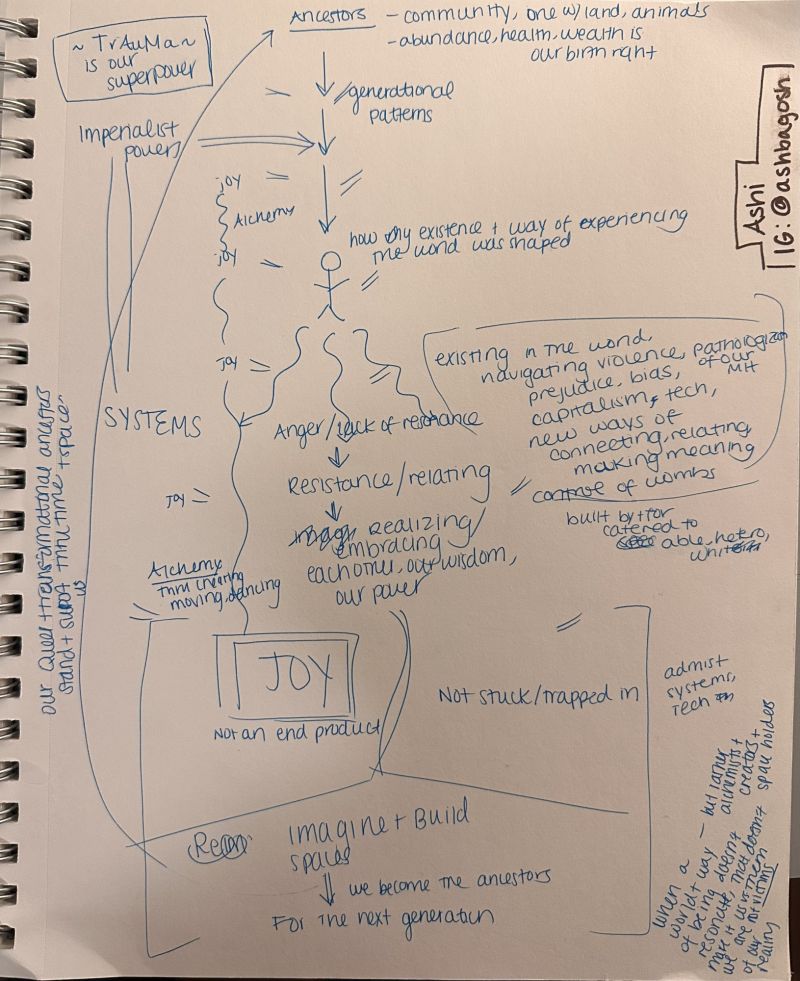

Beyond the Binary of Trauma

By Ashi Arora

Holding a safe space

In order to ‘address trauma and share tools of peace’, as Adwaita intends to, this workshop needs to constitute a safe space, i.e. ‘a place or environment in which a person or category of people can feel confident that they will not be exposed to discrimination, criticism, harassment, or any other emotional or physical harm’ (Oxford Dictionary). The process of going beyond the binaries is really about going beyond oppressive images that we don’t necessarily realise structure the way we see ourselves and others. As a queer and neurodivergent artist, Adwaita is particularly aware of the violence of exclusion and oppression, and therefore attentive to ‘the process of figuring out what a safe space can look like’:

‘Basics: avoiding misgendering, showing a note on how to share screen space (have a stable camera and sound, don’t have a light shining on screen), adding some simple breathing exercises, acknowledging that emotions can pop out.’

When I asked Adwaita how they dealt with potential conflicts or tensions that can arise, they answered:

‘The workshop is designed in a way to prevent conflicts: we are challenging the binaries. Also I invite participants to keep a boundary on what they share or not. They can disengage, and I can ask them to put trigger warnings.’

This idea of staying aware of what you share with others seems to me particularly important: Petra Ardai, an artist practitioner that facilitated the first Agora with U+ also insists on this issue. It reminds us that being in a group, in a space-time of vulnerability and co-creation, doesn’t mean that one must share whatever comes to their mind. Participants are responsible for one another, and responsible for what they bring into the collective space. In return, the group can take on the load of certain emotional difficulties and negativities that come up for the individual.

Another necessary condition of safety for marginalised groups is the strict limitation of any kind of hate speech*.

The message is clear

Binaries, you say?

Adwaita Das’s method is quite different from what we are used to in the Collective Creative Practices project: participants don’t really co-create together; the transformative intention is focused on care and individual wellness; the process is non-directive, leaving participants free to interpret, remain silent – or even leave. It then highly depends on the facilitator’s capacity to insufflate rythm, energy and creativity, and on the participants’ willingness to be active. This can be disturbing to some of us who are used to following a (more or less) designed process, with an online whiteboard and specific tools; who want to understand where this is going and what it is for.

Maybe adding a time of reflection on what is a binary in narratives and how they give meaning to our – own and common – world could help us question the very way we define them, and probably understand that what we consider dominant binaries are not universal, objective, and are, ironically, more complex and in evolution than what we think. For example, French anthropologist Françoise Héritier pointed out that warmth and cold can be seen as respectively negative or positive depending on the culture and context. Some societies associate the feminine with warmth in order to devalue it, while others will make the same sexist statement while associating it with cold. In the end, what matters is not so much the content of the image as the way in which it is embedded in a sexist society.

The Calling of Saint Matthew by Caravaggo. Playing with light and dark.

In the name of poetry

The beauty of this creative exercise is that we (most of us) managed to create and share with others a little of our own personal poetry.

The future here is certainly not something to predict or to know, but a place of possibilities for peace, for the co-existence of all our complex identities, that is made possible through the process of questioning our norms, rewriting our symbols, imagining beyond our rigid – often oppressive – categories. This reminds me of a phrase by queer theorist Yener Bayramoğlu:

‘Queer theory helps us to not take these identities as fixed, stable, and essential categories but maybe as temporary vessels on our way to a better future that need to be always abandoned, dismantled, redesigned, and whose doors need always stay open for people who were excluded before.’

One thing is certain, liminality* is a breeding ground for poetry!

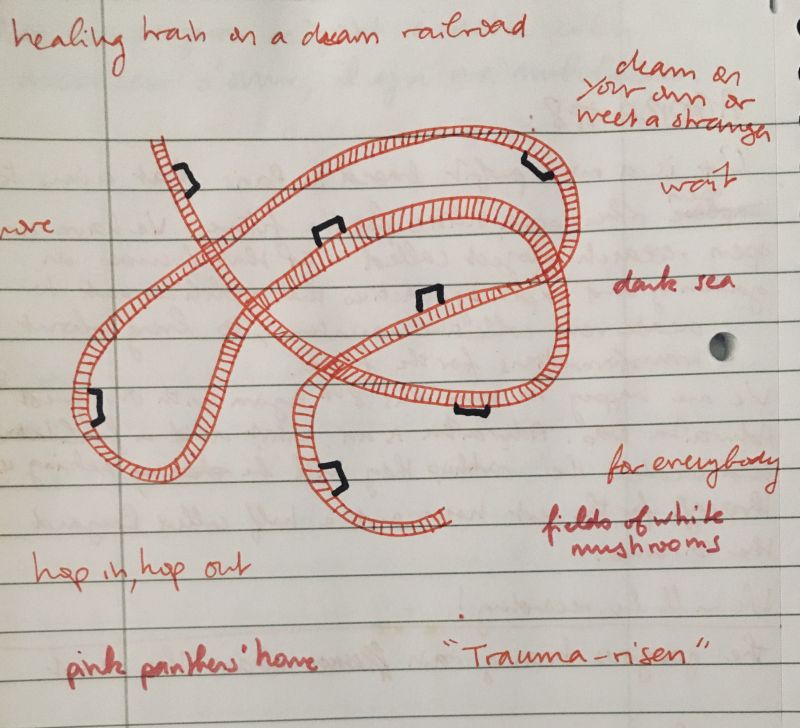

Trauma-rise: the healing dream train.

By Juliette Grossmann

This online agora took place on October 31, 2023, as part of Narratopia’s Collective Creative Practices project. It was organized by the Plurality University Network (U+), and facilitated by Adwaita Das.

Article written by Juliette Grossmann

*Glossary

Hate speech: “any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.” United Nations definition.

Liminality: this concept was coined in 1960 by ethnologist Arnold van Gennep, referring to the middle stage of rites of passage: the moment of transition, of in-between. During the liminal stage, the participant’s identity, their relationship to their environment, family, and, more broadly, society, as well as their relationship to time, space, and existence as such, is in flux. Liminality refers to a state of flux and in-betweenness in which the dominant or governing logic of a given situation is temporarily suspended. Queer and trans approaches unsettle existing binary constructs, and foreground an everyday lived, experiential realm of in-betweenness that brings new stakes into the currently conceptualized political dimensions of liminality.